Text: Alf Inge Molde

Imagine that your arm hurts, and you see a doctor for help. The medical expert listens to your story, asks follow-up questions, and performs an examination. She now has many alternatives: Based on the examination and her experience, she may set a diagnosis, recommend treatment and perhaps prescribe medication.

If, on the other hand, the physician is unsure, she may order a CT scan of the arm for a better assessment. By using x-rays, the machine produces precise and sharp images of the tissue. These images are stacked on top if each other, and provide a picture of the tissue underneath the skin.

If the doctor is still not satisfied, the next step is to perform a MRI scan. This scan provides a very detailed and multi-dimensional digital image, which may reveal whether there have been any changes to the patient’s muscles, connective tissue or central nervous system.

MRI scans may also uncover changes to the skeleton, heart, chest, blood vessels, urinary tracts and bowel organs. The technology thus provides a complete, multi-dimensional picture of whichever part of the body one wishes to study.

An emergency management system is not that different from an organic system as one might think.

“Today’s emergency response plans, which are based on risk- and vulnerability analyses and defined situations of hazard and accident, correspond to an image provided by CT scans. By simplifying the world and a variety of situations, they provide an overview of input values and the expected outcome from adhering to the plans. They usually do a very good job,” says security researcher Riana Steen.

But by placing the plans under scrutiny, we see that they are based on a set of preconditions that over-simplify the world and under-communicate certain factors. When faced with unforeseen, confusing and complex crises, these plans may fall short.

Work as imagined, work as done

The analyses are too coarse. Or, in the scientist’s own words: “Work as imagined doesn’t necessarily harmonise with work as done.”

To fully understand how the response process works in practice —and thereby to ensure a deeper understanding of how the emergency response organisation may succeed or fail under different conditions — one has to consider far more factors than is common today.

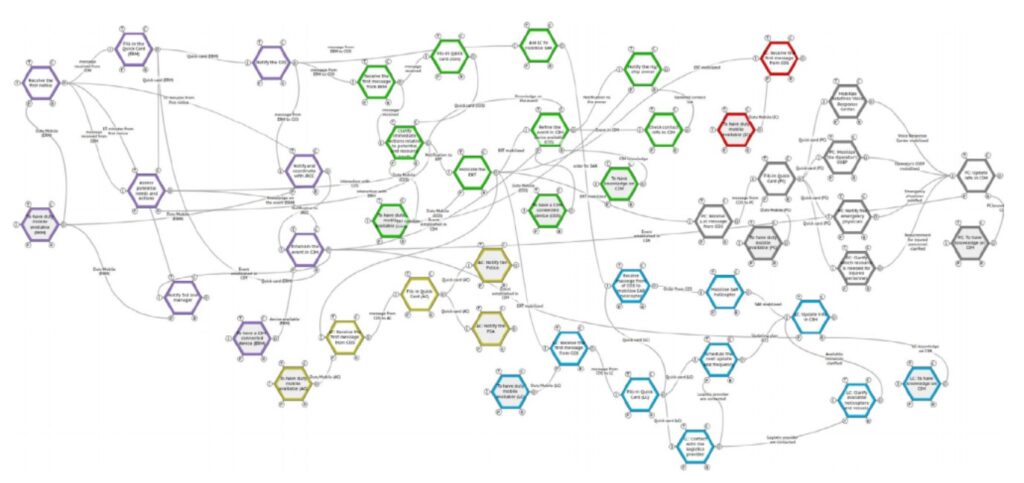

This method, introduced by the Danish security researcher Erik Hollnagel in 2012, is called Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM). Hollnagel has for a number of years played a principal role in the development of Resilience Engineering, also known as Safety-II.

READ MORE ABOUT SAFETY-II HERE: Studies OFFB and Safety-II (internal link, only in Norwegian)

The purpose of FRAM is to model complex socio-technical systems, and provide answers to how resilient an organisation and a system are – and thereby to assess how well prepared one is to manage the unknown and the unexpected.

To complete the preceding analogy: The result of a FRAM analysis corresponds to the multi-dimensional image derived from a MRI scan.

A closer look at OFFB

Put simply, traditional emergency response plans are concerned with the input from various functions and processes, and the potential output from these. But the output may not necessarily turn out quite as imagined.

Different variations may yield unpredicted consequences, both immediately and at a later stage. In order to visualise these contextual factors, four additional features are being mapped: Time, control, precondition and resources.

By drawing lines between the six corners of the emerging hexagons, one gets a far deeper understanding of the factors’ interconnectedness.

Together with researchers Riccardo Patriarca and Guilio Di Gravio, Riana Steen last year conducted a FRAM analysis of OFFB’s 2nd line emergency response plan, and the way the 2nd line handled a hydrocarbon leakage incident on an offshore platform in 2017.

Both Italian researchers are employed by the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Sapienza University in Rome. They are among the leading scientists in Europe within the field of resilience.

In their study, the researchers compared “work as imagined” with “work as done”, seen through the multi-dimensional FRAM lens.

Their analysis has been included in the research article «The chimera of time: Exploring the functional properties of an emergency room in action», which was published recently in the international journal «Contingencies and crisis management».

The article is available for free here (external link): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1468-5973.12353

Several goals

The article has several goals, says Steen. One of them is to provide a step-by-step guide to how the FRAM method may be utilised to map systems and organisations in practice.

Another is to visualise the consequences of changing preconditions, and demonstrate how changes to one part of a system may affect the end result and outcome.

“The method underlines the complexity of emergency response work. We take so much for granted. But what if the infrastructure doesn’t work? What if the on-duty staff is exhausted? And what happens if one decides to postpone a decision because some information is missing?"

“Time plays a crucial role. In order to achieve the desired outcome, one may have to take action within ten minutes. If not, it may be too late. Training is also a prerequisite for being able to respond fast enough. Through the FRAM method, we are able to see how varying preconditions affect functions ten steps down the line. Context is very important,” Steen explains.

It is a demanding job, she acknowledges. It also requires a certain degree of expertise and an organisation that is willing and open to scrutiny. The rewards, however, may be great. The method provides management with a unique, in-depth understanding and an overview of success factors. It enables them to see what could be done more efficiently, and to identify which parts of the systems should be improved.

By capturing what may be hidden between the lines, it is possible to enhance the quality of the planning as well as the tasks carried out.

Continue planning, while introducing more dimensions

The scientific field of resilience and FRAM is still relatively new, but it has been applied in pioneering sectors such as aviation, the chemical industry, nuclear power generation and the oil and gas industry. Steen has also used the method to analyse Egersund municipality’s response plan for managing floods, as it was put into practice during the extreme weather “Synne” in 2015.

The article is available for free here (external link): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0951832020306517

“Does this mean that today’s emergency response plans are not good enough?”

”The plans we have today are generally good. They cover normal situations, the ones we experience most often. But the power of this method is demonstrated when faced with the unexpected. And this is the direction the world is heading, with more unexpected incidents occurring, and systems becoming increasingly complex. We therefore have to keep on making emergency response plans, but maybe develop them from a more multi-dimensional perspective, using for instance FRAM as a tool,” says Steen.

Read more (internal link, only in Norwegian) Suksesskriterier for god koordinering